All too often in industrial disputes, the two sides appear to get locked into a mental attitude of “losing both ways”. One or both sides decide that they can’t get what they want, and so they make it their business to punish the other side. This then becomes a more important objective than thinking round the problem to find a new solution which suits everybody.

I was reminded of this when reading in the Guardian that the Public and Commercial Services union has warned of new strike action over its ongoing dispute concerning pay, pensions and working conditions (here). It has said it will ballot its 250,000 members starting tomorrow. The union, led by the redoubtable Mark Serwotka, has already held three previous days of strike action, and is now focused on a review of working conditions which it says threatens working hours, sick pay and holiday benefits.

Given the current Government priority to manage the Public Sector deficit, this is not an argument which the Union is likely to win – the Government is determined to rein in Government spending. So strike action may seem like a good way of punishing the Government, even though it does not bring about any greater prospect of negotiating success, is disruptive for members of the Union and the General public, and may well harden Public opinion against the Union cause. This is losing both ways in action. I mention this phenomenon in my forthcoming book on negotiation, “The Yes Book”, published on Random House on March 28th. Here is a story, originally written for the book, though I subsequently took it out, about the UK Miners’ strike of 1984 which illustrates the futility of taking a “losing both ways” approach to negotiations in industrial relations…

1984 Miners’ Strike – No Loser Wins

In 1966 Britain produced some 188 million tons of coal from 480 mines, but by 1984 coal was no longer seen as a viable option in a changing energy market. Britain was turning to North Sea Oil and Gas, and the Government chose to implement the recommendations of a 1974 report into Nationalised Industries which concluded that it would be cheaper for the UK to import coal from Australia, Columbia and the US, than to extract it in the UK. The National Coal Board announced that 20 pits had to close with the loss of 20,000 mining jobs.

This was not what miners were used to. In both 1972 and 1974 the Miners had held successful strikes and gained huge pay rises. In 1974 their disruption had brought about a 3 day working week and the downfall of the Conservative Government before the incoming Labour administration meekly accepted that they should be awarded a 29% pay increase.

In March, 1984 many miners began to take strike action in the areas affected by the planned closures. The leader of the National Union of Mineworkers, Arthur Scargill called for local strikes to be made national. On March 15 a miner died on a picket line inflaming tensions. The strike spread and affected Scotland, Durham and Kent. There was a notable exception in Nottinghamshire and the Midlands where miners were less affected by the planned closures and voted against the strike. By March 18th 3,000 police officers had been assembled at Nottinghamshire to control flying pickets from other areas who were trying to prevent the Notts miners working.

The NUM declined to organise a national strike ballot – and this increased rhetoric on both sides of the dispute. Arthur Scargill was quoted as saying “the policies of this government are clear – to destroy the coal industry and the NUM”. Mrs Thatcher famously retorted that the strike was “an attempt to substitute the rule of the mob for the rule of law”. Lord Tebbit called the strike “a war on democracy” and Lord Lawson apparently declared that preparing to take on the miners had been “just like re-arming to face the threat of Hitler”.

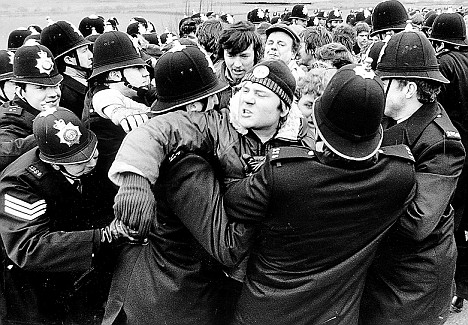

The strike will be remembered for violent clashes on the picket lines. It cost £200 million to police – equivalent to £500 million at today’s values – and involved officers from 30 forces. Some 9,500 people were arrested, including Scargill himself. By early 1985 though, a trickle back to work had begun. It had been a harsh winter and families of many striking miners were unable to afford heating bills. The NUM’s funds had been seized in October 1984 as the strike had been declared “illegal” on account of the lack of a national ballot, and so many families were struggling without an income. By early March 40% of miners had returned to work, and on March 3rd, by a tiny majority the NUM voted to end the strike.

The strike will be remembered for violent clashes on the picket lines. It cost £200 million to police – equivalent to £500 million at today’s values – and involved officers from 30 forces. Some 9,500 people were arrested, including Scargill himself. By early 1985 though, a trickle back to work had begun. It had been a harsh winter and families of many striking miners were unable to afford heating bills. The NUM’s funds had been seized in October 1984 as the strike had been declared “illegal” on account of the lack of a national ballot, and so many families were struggling without an income. By early March 40% of miners had returned to work, and on March 3rd, by a tiny majority the NUM voted to end the strike.

The consequences of the strike are well documented. By 2009 Britain had only 6 operating coal mines. Unemployment in former mining communities reached around 50% during the late 1980’s. There is still bitterness in such communities at what is seen as the ferocious intransigence of the Government during the strike and the “punishment” that was meted out by the Government in the wake of the crushing of the strike, with little strategic or financial assistance to realign mining communities or re-skill former employees. Equally, analysts have lined up to blame the NUM and Arthur Scargill for their stubbornness during the strike. Andrew Marr in his book “A Modern History of Britain” describes Scargill as “incompetent” for calling an early strike and holds him responsible for the decline of the coal industry. The Guardian, writing its editorial on the 25th anniversary of the strike called the miners “lions led by donkeys” and said that the miners’ failure to call a national ballot “guaranteed that Mrs Thatcher’s victory would be total.

Whatever the rights and wrongs of the dispute we can safely say that the 1984 Miners strike was a fine example of industrial negotiation done the “old fashioned way”. No prisoners, no compromise, not an inch given by either side. And the result? No winners. For the miners the manifestations of defeat are obvious. However, the Government is estimated to have spent as much as £30 billion at today’s prices on its programme of closures, on policing the strikes, and on subsequent redundancies and welfare payments. Meanwhile the UK has become heavily dependent on overseas sources of energy as North Sea Oil declines. One of the costs was the closure of the Coal Research unit at Cheltenham in 1994 which had previously led the world in the development of clean coal technology and carbon capture. The 18 years of lost research in that area might have generated a whole new industry for Britain as the world struggles to control the effects of carbon emissions on climate change…”.

Losing both ways has been a costly strategy for everybody involved…